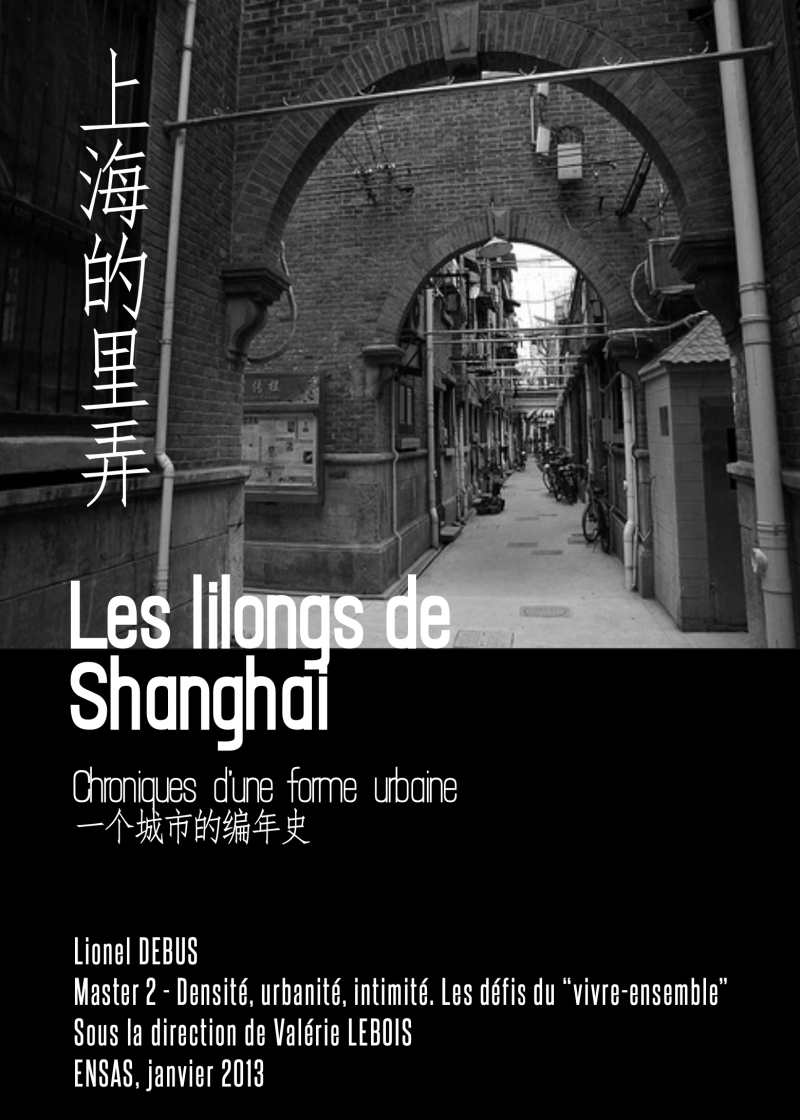

The lilongs of Shanghai: Chronicle of an urban form

It was during a ten-day workshop in October 2011 that we discovered Shanghai and its lilongs. And what a discovery! Shanghai is a dynamic city. Populated. Dense. The city resounds with the horns of cabs, the cries of street vendors, and the music of stores of all kinds. And at all hours, everywhere, on every street corner, at every subway stop, you come across a human tide of busy Shanghai people. In 2010, the Shanghai Statistics Bureau estimated the city's population at more than 23,000,000, with a density of 3,627.5 inhabitants per km2. And its urban landscape is still changing. Since the 1980s and the end of the "communist winter", construction has resumed and high-rise housing complexes and concrete bars are flourishing in the city. The outskirts were the first to be affected, pushing back the limits of the city ever further in a dull architectural landscape. Then, in the 1990s and with the opening of Shanghai to the market economy, it was the turn of the city center to see the towers rise from the ground.

An urban form that best meets political and economic expectations in terms of land profitability in the face of a pressing demographic phenomenon, the complexes of towers and housing bars nevertheless embody for many Shanghaiers and Chinese the modernity of a Communist China open to the market economy. But this is not the one and only dense, modern urban form that Shanghai has seen, and history seems to be repeating itself, for before that there was the lilong: 里弄.

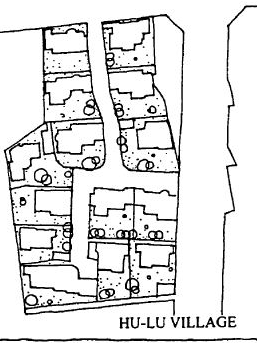

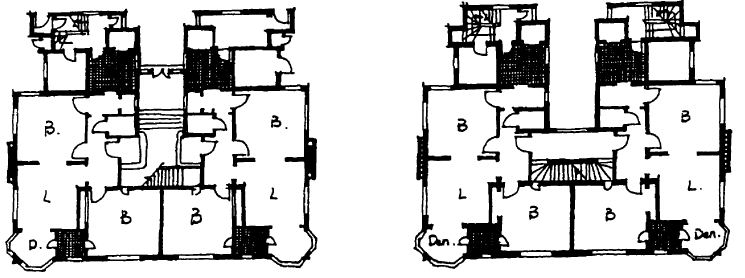

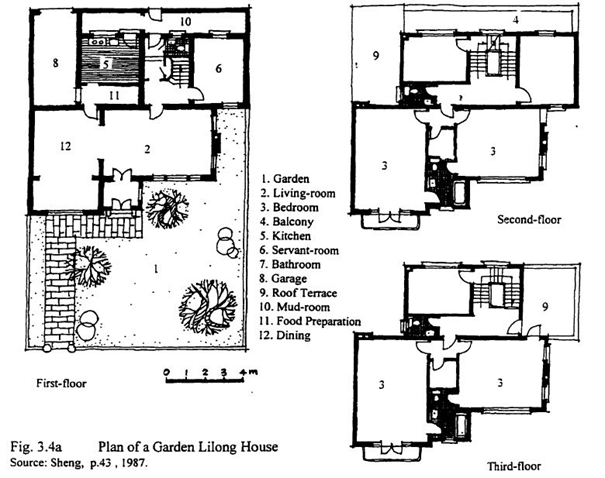

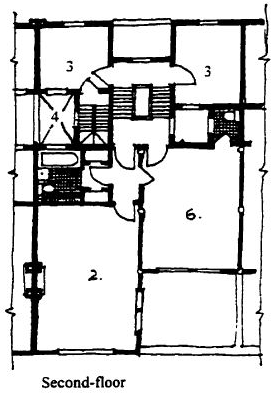

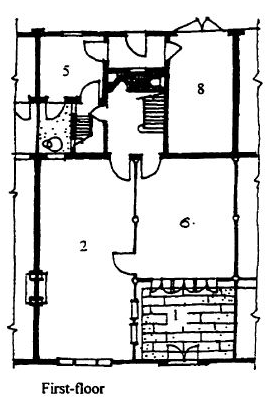

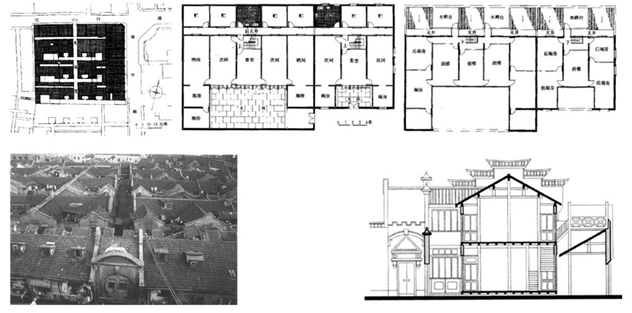

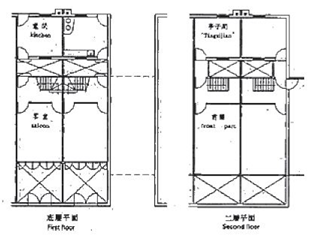

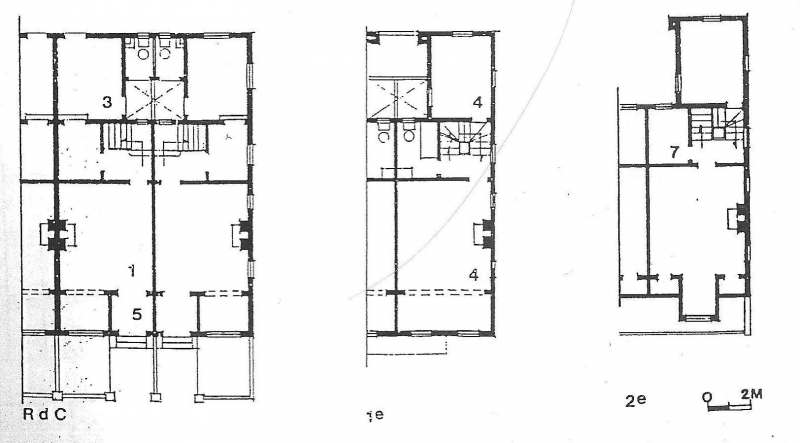

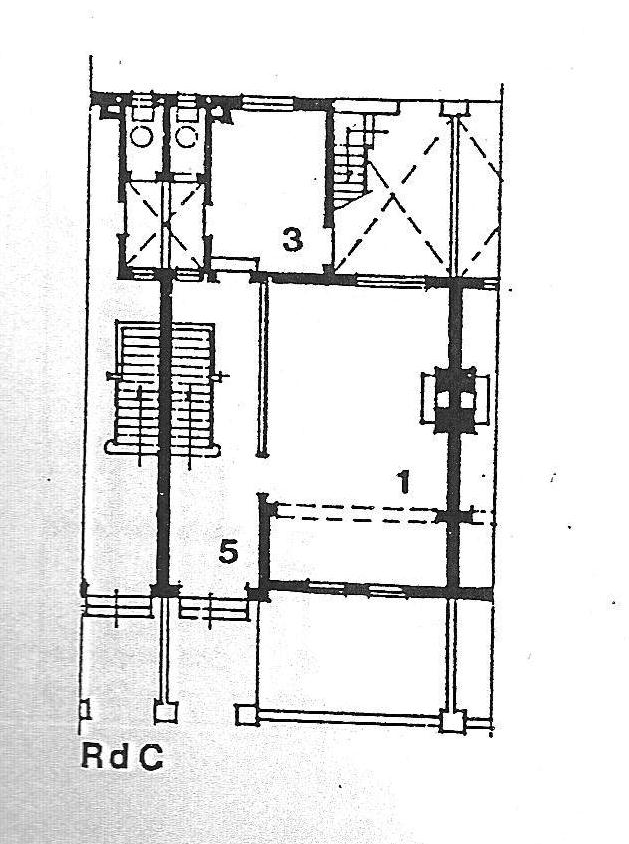

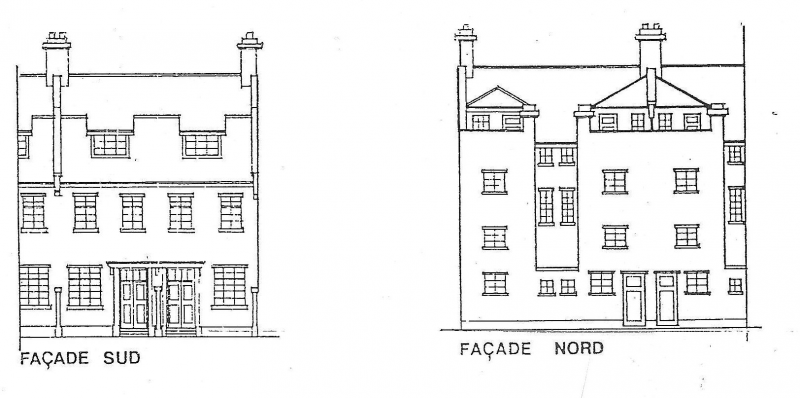

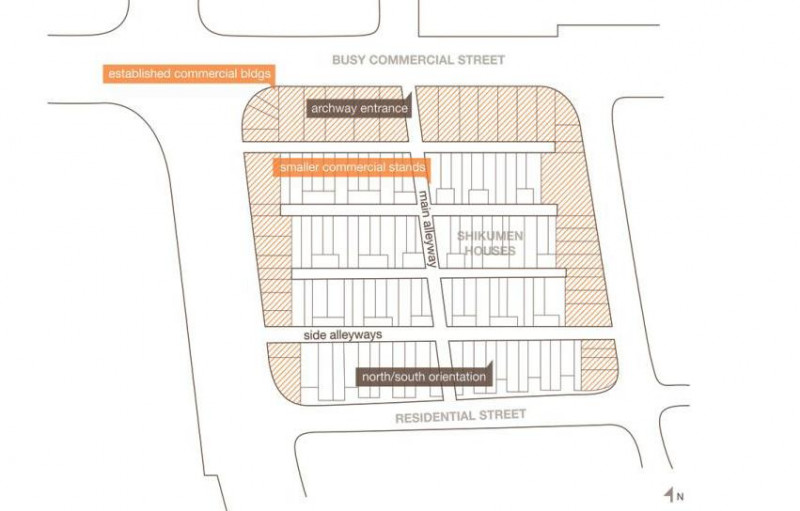

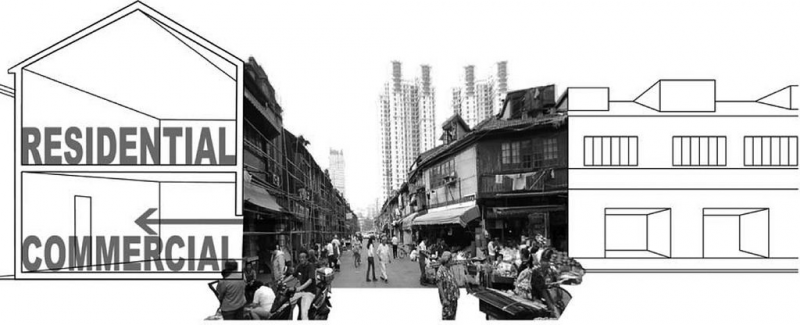

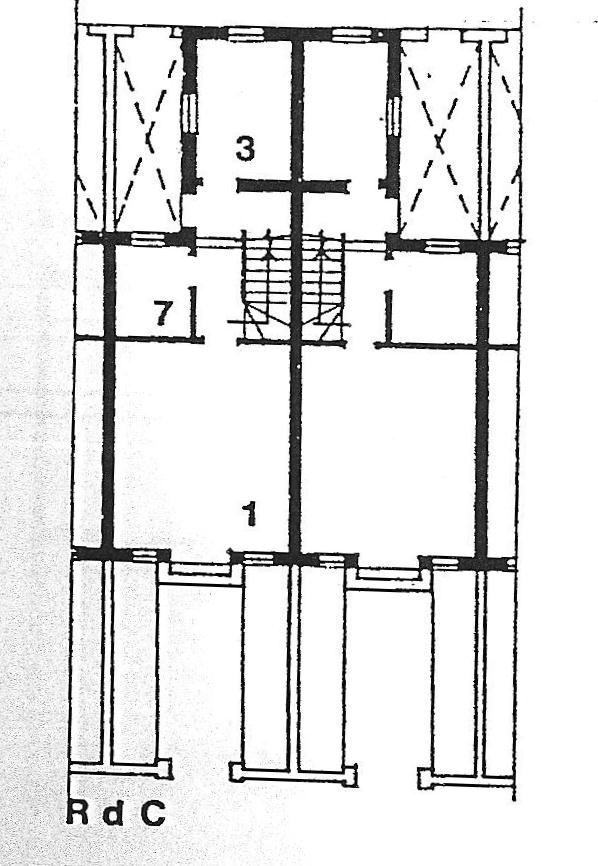

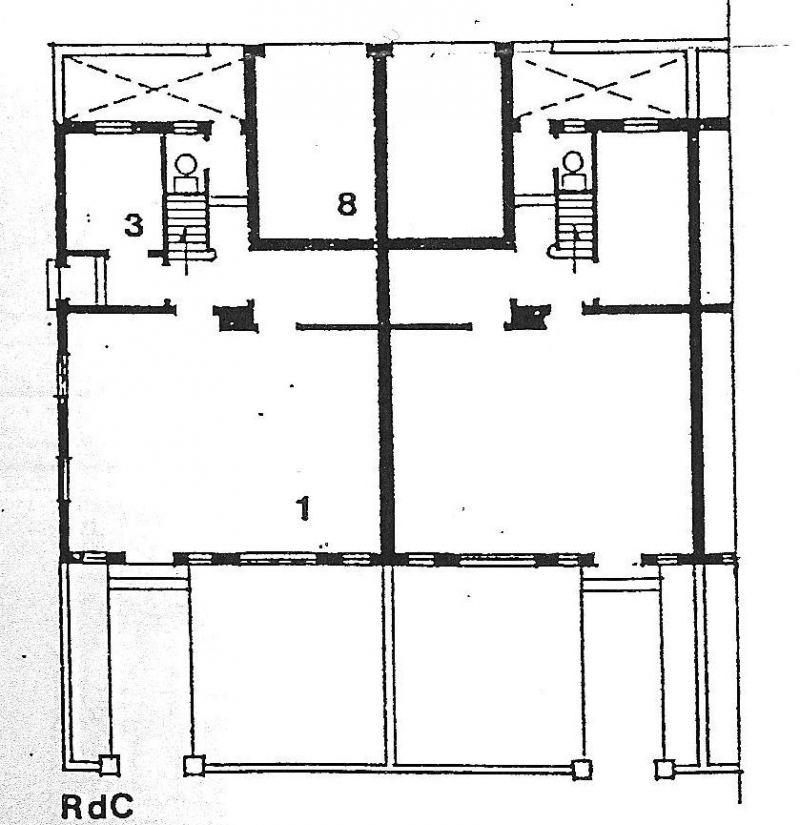

The lilong is that urban fabric that still makes up most of the Shanghai of the Concessions, in the heart of the city. The explanation is historical: Shanghai, a "textile" city, is made up of a network of avenues, streets and alleys that intertwine and intermingle, overlap and grid it at different scales. These major axes were created by the Westerners to mark the successive limits of their concessions and to ensure their control and sovereignty. As for the Chinese, they immediately filled in the gaps, furnished the spaces, inhabited the places, organized their habitat in communities welded around extremely dense networks of sometimes tiny alleys, with their roundabout accesses, back doors, dead ends and passages. "The first laid the framework, the second wove the fabric," comments Pascal Amphoux. And the French architect and geographer adds, "Li (里) would be related to the concept of neighborhood unity, community. Long (弄) has a more spatial meaning and refers to the idea of alley, passage." And by combining two concepts - one social, the other spatial - we get a simple and effective description of lilong as a characteristic mode of inhabitation centered on the semi-public, semi-private spaces of the alley. As for their physical form, the French architect and sinologist Françoise Ged, author of a thesis on the subject, describes the lilong as a subdivision of "one- or two-story terraced houses, arranged in parallel rows and served by a network of hierarchical alleys," a scheme not unlike the English lanes of the same period, but closer, originally, to Chinese vernacular forms.